A Neighborhood’s Long Struggle with an Offensive Landfill

A satellite image of some the beautiful homes that are just a baseball throw from Holcim’s Lordstown Landfill. The toxic gases and dust do not have to travel far to impact the residents. Lafarge excavated the original phases of the landfill 50 feet deep and through two groundwater zones. 40 million gallons of water/year gets […]

A satellite image of some the beautiful homes that are just a baseball throw from Holcim’s Lordstown Landfill. The toxic gases and dust do not have to travel far to impact the residents. Lafarge excavated the original phases of the landfill 50 feet deep and through two groundwater zones. 40 million gallons of water/year gets […]

Trending Shows - Trend Magazine originally published at Trending Shows - Trend Magazine

A satellite image of some the beautiful homes that are just a baseball throw from Holcim’s Lordstown Landfill. The toxic gases and dust do not have to travel far to impact the residents.

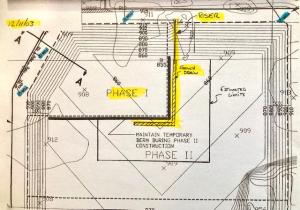

Lafarge excavated the original phases of the landfill 50 feet deep and through two groundwater zones. 40 million gallons of water/year gets into the landfill. Pumps were used to keep the sidewalls from collapsing. In 2015 the OEPA caught the landfill pumping the water.

Besides the wells pumping 24/7, Lafarge had a massive trencher install a bentonite barrier around the entire landfill. No luck. The groundwater still comes up from the bottom of the landfill.

Part I: The Nightmare Begins

— William Dray, Village of Lordstown Councilman, 2003

CLEVELAND, OHIO, UNITED STATES, April 11, 2022 /EINPresswire.com/ — In the mid-1990’s, a young, hard working couple bought a few acres in rural Lordstown, Ohio to build their perfect home and raise their children. It took several years to finish their homestead with outbuildings, a private patio, pool and manicured gardens. Their neighbors’ homes were also newer and comfortably spaced apart. They had their idyllic setting and it was only minutes from Interstate 80 and the Ohio Turnpike.

This is what so many Americans want: space, privacy and clean country air with good access to markets. So it was for the young couple until 2002. That is when Lafarge, aka LafargeHolcim and now Holcim US, announced that they were opening a demolition waste landfill across the street.

A rail yard has been on the Lordstown property since World War II and trains brought slag waste from the many Youngstown steel plants. The slag was processed into aggregate, then resold as road base for highways. Miles of the original Ohio Turnpike was underlain by aggregate from Lafarge’s plant.

When the steel industry collapsed in the 1970’s, the “rust belt” was born and the in-bound slag stopped. The 20 million tons of slag stockpiled at the site continued to be processed and marketed. After another 25 years of operation, the property was mostly cleared.

In 2002, Lafarge management saw a high-reward opportunity. The Lordstown property had ready acreage and is connected to the CXS rail system which could haul waste from anywhere in the United States. Better yet, political and environmental pressure had forced many of the landfills in the East Coast to close. Licensed disposal space was at a premium and waste pricing skyrocketed.

The investment must have appeared as a no-brainer for the world’s largest cement producer. They already had bulldozers, endless heavy equipment and were experts at mining. How difficult could the landfilling business be?

A landfill license required a hydrogeologic evaluation to ensure the local groundwater was protected. Soil testing was preformed and evaluated by Lafarge’s consultant, Bowser Morner. Several clay zones were encountered in the subsurface which usually indicates a good seal for groundwater from waste drainage called “leachate”.

In 2002, Lafarge filed for its demolition landfill license from the Trumbull County Health Department, who was granted licensing and inspection authority by the Ohio EPA.

The residents of the Village of Lordstown were outraged. Many, like the young couple, lived directly across the street from Lafarge—literally, a baseball throw away. Under pressure, the Village Council filed a lawsuit, Case 2002-cv-2209, against Lafarge, the Ohio EPA, and the Trumbull County Health Department who issued the license.

Corporate attorneys and a platoon of consultants explained the geology was great, the design was flawless and dozens of jobs would be created. Several Village Councilmen wanted environmental tests completed first. Councilman William Dray contacted the Ohio EPA about taking baseline stream samples. In November 2003, Councilman Dray reported, “Their answer was that they couldn’t do it, that they can’t test all the water everywhere. I don’t want them to test everywhere. I want them to test these three creeks…”. The tests were never completed.

The case dragged on but the Village was outgunned. The parties settled on April 4, 2004.

The settlement gave the Village of Lordstown 10 cents/ton of waste. Lafarge received their landfill license but would be restricted to piling the waste “only” 200 feet, making the landfill the highest point in the county. The neighbors, who were not privy to negotiations, received a complaint hotline to the landfill and three seats on the new Village-Citizen-Landfill Communication Committee.

A complaint hotline to the facility causing the complaints proved absurd. After 12 million tons and $1.2 million in waste fees, the Village has called for a committee meeting a total of three times in 18 years.

Shortly afterward, the Village filed a contempt case regarding the size of the landfill. The Village believed the landfill would be 30 acres; but they must have been “confused” as Lafarge claimed it was 130 acres. The Village was worn down with legal demands and costs and dropped the case in 2006.

Such is the profile of remorseless corporations in rural America: swaggering behemoths with billion dollar fly swatters.

Construction started. Thirty acres of the site were excavated 50 feet deep to generate additional disposal space; five million tons of earth moved. Not known by the public until years later, the excavation cut through not one, but two, groundwater tables. The engineering exercise of “connecting the dots” of the clay data proved faulty—porous sand was everywhere.

Demolition landfills in Ohio do not require the plastic liner systems mandated by RCRA for garbage landfills. Demolition landfills were, and still are, considered “less dangerous” to the environment and public and only require clay liners. Little do they know.

In fact, Lafarge installed no liner whatsoever in the original 30 acres. Groundwater poured into the mammoth hole from the bottom and the sides. Not thousands of gallons or hundreds of thousands of gallons, but 40 million gallons a year. Lafarge surrounded the massive crater with pumps in direct violation of Ohio EPA regulations. They pumped 24 hours/day to keep the steep sidewalls from collapsing—until the hole was filled with waste.

In 2005, Ohio passed House Bill 432 which created an enormous $1.80/ton demolition fee structure for landfills. The Trumbull County Health Department’s share is $0.60/ton. After 17 years and $6 million from Lafarge, the Health Department typically approves Lordstown Landfill’s annual license like clockwork.

Since 2005 the Health Department’s programs have expanded. But not the landfill inspection program. It performs a one-man, 45-minute inspection every 90 days per the regulatory minimum requirement. The other 89.97 days are LafargeHolcim’s.

Demolition waste contains vastly more pollutants than environmental regulators appreciate. However, they do know that demolition combined with water creates toxic hydrogen sulfide gas. And Holcim’s Lordstown Landfill, holding millions of tons of waste and hundreds of millions of gallons of groundwater, is a perpetual toxic gas machine.

Upcoming: Part II Denial is Not a River in Egypt

Markus Aurelius

Citizensagainstlordstownlandfill.org

email us here

Visit us on social media:

Facebook

![]()

Trending Shows - Trend Magazine originally published at Trending Shows - Trend Magazine

,

,